04/22/2019

The American Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s has been well-documented by historians.

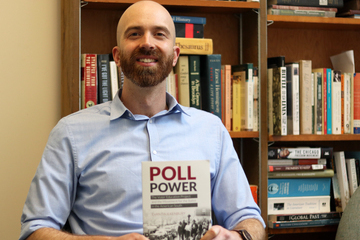

SUNY Cortland’s Evan Faulkenbury, an assistant professor in the History Department, has found a story that had gone largely untold; a secret effort that helped hundreds of thousands of illegally disenfranchised black voters cast ballots in southern elections. He shares that tale it in his forthcoming book, Poll Power: The Voter Education Project and the Movement for the Ballot in the American South.

Prior to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, African Americans and racial minorities were systematically denied the right to vote, through Jim Crow laws at the state and local levels, despite those rights being protected by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

A number of civil rights activists convinced nonprofit and philanthropic foundations to donate money toward voter education and registration efforts. With the support of activists, financial donors and the Department of Justice, under attorney general Robert F. Kennedy, the Voter Education Project (VEP) was launched in March 1962.

From that time through October 1964, the VEP registered approximately 688,000 black southerners by spending $855,836 on 129 projects throughout the 11 states that had made up the Confederacy in the Civil War. The money, which came largely from liberal, white northerners, paid for fuel, food for volunteers and for people to canvass neighborhoods and bring people to their local courthouse to register to vote.

“All of that was necessary because at that point in time, black Americans had very few protections for voting,” Faulkenbury said. “To organize a campaign like that cost money. The VEP provided that kind of backing and funding and resources that made the Civil Rights movement happen, in a sense.”

The reason the VEP has been mostly left out of the history of the Civil Rights movement was the secrecy with which it operated.

“It was unique because they had to be super careful,” Faulkenbury said. “That’s why no one has ever heard about the VEP. They were intentionally behind the scenes and clandestine because they got this special tax exemption from the IRS. They were worried that once conservatives sniffed this out, they were going to kill it and eventually they did. It lasted after that, but they hurt it pretty bad in 1969.”

Although the Tax Reform Act of 1969 intentionally undercut the VEP’s funding, the organization continued doing voter education and registration work until it closed in 1992.

One of the VEP’s leaders in the 1970s was U.S. Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.), a major figure in Civil Rights activism in the 1960s. Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from 1963 to 1966, spoke at the March on Washington and was beaten by police before a planned march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. in 1965. He is currently chair of the House Subcommittee on Oversight, a member of the House Ways and Means Committee and the senior chief deputy whip for House Democrats.

“I was able to interview him about it and it was really cool,” Faulkenbury said. “Most people just want to talk to him about the things he’s already talked about a million times, but I think I was one of the first to ask him about the VEP.”

Faulkenbury has also included his students in his research on this topic. Steven Lawson, professor emeritus of History at Rutgers University, gave Faulkenbury a briefcase full of VEP documents that had been sitting in his attic for years. SUNY Cortland students are working to digitize this information and make it freely accessible online to help preserve the role of the VEP in the Civil Rights movement.

A digital map of the VEP’s voting registration efforts is available on Faulkenbury’s website.

Poll Power will be published by the University of North Carolina Press in May. It is available for preorder at UNCPress.org and Amazon.com.