09/11/2018

To many people, the ingredients listed on their shampoo bottle look like an alphabet soup of unpronounceable chemicals.

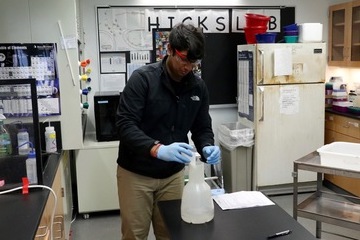

But not to Assistant Professor Katherine Hicks and her chemistry students. And they are fascinated by one of those in particular: nicotinic acid.

Nicotinic acid is an example of a class of organic compounds called N-heterocyclic aromatic compounds (NHACs), which are found in a variety of personal care products and pharmaceuticals. Although they won’t hurt your hair, this class of small molecules ultimately winds up in soil and water as pervasive environmental pollutants that pose health and mutagenic risks to aquatic life.

Thanks to a collaborative three-year grant of $290,796 from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Hicks and her students, as well as a team at the College of Wooster (Ohio) will investigate a biochemical solution to this problem. Common soil-dwelling bacteria contain enzymes that are involved in breaking down nicotinic acid. Using genetic technology and structural protein crystallography, Hicks hopes to further discover the mechanisms behind how bacteria in soil and water degrade pollutants.

Ultimately, they hope to find a way to use otherwise harmless bacteria to gobble up unwanted nicotinic acid in the environment.

That goal is part of a larger trend. The field of bioremediation is growing, as scientists look to find ways to remove harmful elements from the environment without using additional chemicals.

“There are harmless bacteria that live in the soil naturally and you can engineer them so that they can break down these pollutants rather than introduce chemicals or some other method of removing them,” Hicks said. “In order to engineer those bacteria, you have to take a step back and understand their natural way of breaking down those types of molecules.”

Protein crystallography will allow Hicks and her students to determine the position of every atom in the enzymes produced by the bacteria. From there, they will be able to confirm the functions of enzymes in soil-dwelling bacteria that digest nicotinic acid.

Part of the grant money will also allow Hicks to take her undergraduate assistants to the annual Buckeye Women in Science, Engineering and Research Institute (B-WISER) summer camp hosted by The College of Wooster. The week-long camp is aimed at middle school-aged girls who are interested in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). Hicks hopes to introduce a younger generation of students to her research as well as inspire them to continue their studies and consider careers in science.

“Seeing women in STEM and female students in STEM encourages girls that they can be in STEM also because they see us as role models,” Hicks said.

Mark Snider, professor of chemistry at The College of Wooster, serves as principal investigator of the NSF grant and works closely with Hicks. In fact, a previous joint project between the two faculty members resulted in a publication in the peer-reviewed journal, Biochemistry, that included a number of undergraduate co-authors from their respective schools.

“Scientists are portrayed sometimes as working by themselves with their test tubes, but really science is super collaborative,” Hicks said. “We’re always talking to other people and we’re working in teams.”

Hicks recalled her undergraduate research experience as a transformative moment in her career. No matter what path her students take after SUNY Cortland, whether it be further higher education or careers in biochemistry, medicine or beyond, she knows that the process will serve them in the long run.

“What I tell my students is that one of the most important things about a science education is that it makes you think critically about problems,” she said. “It impacts your whole life and how you approach getting a mortgage and fixing your car, all of those things. It trains you to think more analytically, which has life benefits.”