03/21/2018

African Americans served bravely in an integrated military during the American Revolution, often fighting for a more literal freedom than their white comrades-in-arms, according to Judith Van Buskirk, a professor of history at SUNY Cortland and author of a unique book on the subject.

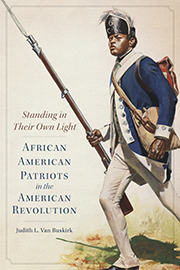

Van Buskirk is the first historian to make extensive use of the Revolutionary War pension records. Her research resulted in the 2017 book, Standing ln Their Own Light: African American Patriots in The American Revolution (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

From both the northern and southern colonies, a large number of free blacks, and slaves released to serve in their owner’s stead, enlisted and served alongside whites as soldiers in Gen. George Washington’s Continental Army in the struggle for independence, according to Van Buskirk.

Decades after the war, to get a pension the veteran had to go to his local courthouse and swear a deposition of what he did in the American Revolution, Van Buskirk said. Often a son, widow or fellow former soldier spoke on their behalf.

“No one has used the pension records to the extent that I have to research the black experience in the American Revolutionary War.”

Using primarily African American sources is new for Revolutionary War research, according to Van Buskirk.

“It’s the closest thing we have to an African American voice in the revolution,” she said.

Van Buskirk shared that voice last month in a special Black History Month presentation at The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. The topic drew considerable media attention to an aspect of the Revolutionary War that few Americans are aware of.

Estimates put the number of black patriots at around 5,000, but Van Buskirk qualifies that figure.

“Whenever you approach numbers as an historian there is always an argument,” she said. However, it’s established that black men served from all 13 of America’s original states.

The war started in 1775 at Lexington and Concord and ended in 1783 with the Treaty in Paris, but in terms of battle action, the major fighting had ended by the fall of 1781.

Pension Acts to reward the former soldiers, passed in 1818 and again in 1832, required them or their families to testify about their experiences with the Continental Army, leading to a motherlode of detailed information about the war offered by men in their early sixties for the first pension act and in their 80s for the second.

“You tend to think of Revolutionary War veterans living during the American revolution but they lived into the early republic, the early 19th century,” Van Buskirk said. “These are old guys in the 19th century.”

The records relate that, originally recruited into supporting roles, African Americans increasingly were drawn into combat as the rebellion intensified, Van Buskirk said. The pension testimonials filed in county courthouses throughout the colonies chronicled their injuries and details of what they endured during key Revolutionary War engagements, as verified by their peers on the battlefield.

“It was thought they wouldn’t be good soldiers, but the fact that they were wounded, that they served in light infantry — the elite corps of the day — and that they earned badges of merit all point to their military prowess,” Van Buskirk said.

In fact, the records established that many of these African American veterans lived long enough to share their proud record of service to their country in the subsequent movement to end slavery, Van Buskirk said. Abolitionists, citing the contributions of black soldiers, adopted the tactics and rhetoric of revolution, personal autonomy and freedom.

“A big argument that’s made in the Black Abolition movement of the 19th century was to remind the white community that their fathers and grandfathers fought in the American revolution and they certainly deserve an equal place in the society that their forefathers helped to found,” Van Buskirk said. “And the black veterans themselves were part of that movement as well.”

Blacks at first were recruited by the rebel side cautiously.

“There were many free blacks from New England,” Van Buskirk said. “And in the beginning of the war, the colonies passed laws that prohibited black men, period, from entering the war. But then as the war dragged on, they let in free blacks. And then, they allowed enslaved blacks who got permission from their masters to join the army. And in those days, if you were called up to service, you could have somebody else substitute for you, and there were masters who got slaves to serve for them. They might serve for money or their freedom. So, there were a conglomeration of free and enslaved blacks who served under Washington.”

Blacks also joined the British side’s effort to retain control of its colonies in America, said Van Buskirk, whose research does not encompass black participation with the opposing army.

“Of course, they were fighting for their freedom,” she said, citing the work of other historians.

“After the British lost, they couldn’t stay because most of them were enslaved and would be taken back by their masters,” Van Buskirk said. “Many got on boats where they ended up all over the world: in Canada, England and some went back to Africa.”

And sadly, the promise of freedom in exchange for patriotic service was often broken by slave owners in America.

In this war, segregation of the American servicemen evolved as the exception, not the rule. Segregated units included one black regiment of about 200 servicemen with white commanding officers called the First Rhode Island and a couple black companies of about 50 soldiers.

The First Rhode Island was planned to number 500 to 800 black soldiers but remained undermanned, Van Buskirk noted.

“The state legislature of Rhode Island passed an act that enslaved men could offer to serve for the duration of the war,” she said. “If they passed muster, they entered service with the First Rhode Island and then they were freemen.

“There was nothing in the law that said they had to get the permission from their masters. So, when men started walking off the fields and into the regiment, the power brokers in Providence decided, ‘We can’t have this,’ and passed another law that closed it down before more men joined.”

Van Buskirk sometimes found that a black serviceman’s testimonial amended America’s record of a key American Revolution battle.

“Pompey Woodward was a new Englander who was present at the Battle of Bennington (Vt.), a part of the Saratoga campaign and a great victory for the Americans,” she said.

“But Pompey Woodward doesn’t tell about the battle itself in his pension deposition but about what happened after the battle. He says, ‘Yeah, I remember after the battle we put all the enemy prisoners into the meeting house. And that night there was a disturbance and our men went in and shot some prisoners.’

“There’s no history that says we went in and killed defenseless prisoners of war,” at that battle, Van Buskirk said. “I had to find some corroboration of this because just because one person says it’s so doesn’t make it so. And I found it; and this apparently did happen. He’s telling us a story that’s quite different from the official report made to the Continental Congress about the battle.

“A private’s view of the war is quite different from the general’s,” Van Buskirk said. “Until recently we often only have had the general’s recall of the experiences.”

These remembered experiences of African American patriots offer a fascinating peek into the past.

“There’s a funny story having to do with Agrippa Hull,” Van Buskirk said. “He was an enslaved man from New England who served a very famous Polish general who joined the American Continental Army, Tadeusz Kosciuszko.”

Kosciuszko brought from Europe an elaborate uniform and a hat with an ostrich plume sticking out of it.

“One night, Kosciuszko was going to go away from camp for a couple of days and Agrippa, whom everyone called ‘Grippy,’ decided to have a party. He put on the uniform and hat and paraded around with everyone congratulating him. Everyone was toasting him and having a fine old time when who arrived at the party but Kosciuszko. So, everybody tore out of there. And there was Grippy, in his general’s uniform, and mortified beyond belief. But Kosciuszko kind of had a sense of humor.”

The general made his underling don the fancy hat again to parade at another general’s party, where a throne was erected for Grippy.

“Agrippa Hull lived a very long life into his late eighties and he regaled his community with tales about the night he did all this, much to the delight of everybody,” Van Buskirk said.

“So, they were human beings, not just a part of a subgrouping. They were men who had a sense of humor and lived life.”

Van Buskirk joined SUNY Cortland in 1997 as an assistant professor in the History Department. In 2003, she was promoted to associate professor and in 2016 to professor.In 1999, she was among only 27 scholars worldwide to be awarded a Fellowship in American Civilizations grant by the New York City-based Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Van Buskirk studied at three New York City historical archives for her resulting 2002 book on American Revolution history, Generous Enemies: Patriots and Loyalists in Revolutionary New York.

She has had numerous scholarly articles, book reviews, article critiques, exhibit critiques and encyclopedia entries published.

Van Buskirk received a Bachelor of Arts in French from La Salle College, and earned a Master of International Business with a concentration in international finance from the University of South Carolina. She earned her Ph. D. from New York University with a dissertation titled “Generous Enemies: Civility and Conflict in Revolutionary New York.”